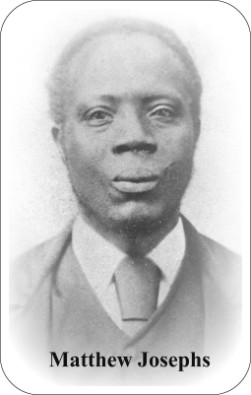

Matthew Josephs

This photograph of Matthew Josephs is the earliest that I

have so far found of a 19th century Jamaican teacher. He

was a teacher in Trinity Ville, in St. Thomas-in-the-East,

in the mid-19th century.

Where he was born ...

The Island of Jamaica has been at all times proverbial

for its beautiful scenery, especially towards its eastern

side. A voyager, for the first

time approaching this part

of the Island, cannot but be delighted with

its green

valleys, and romantic glades; and with the cloud capped

peaks

of the Blue Mountains in the distance. Sailing

southward from Morant

Point, the seaports of Port Morant, Morant Bay, and Yallahs Bay

will

successively be passed. On reaching Plumb Point, Kingston the capital of

the Island, will

appear in view then will also be seen at a distance,

and at an elevation of 4,000 feet above the

level of the sea, the

cantonment of Newcastle, the only military station in the Island in

which

white troops are kept. Beyond a ridge of hills on the western side

of Newcastle, is a broad

and. beautiful valley, containing coffee

plantations; on one of these, called Rose Hill I was

born, on the 25th October 1831.

Ancestry and childhood.

My father was the eldest son of Agullon, a Prince of one of the Eboe

tribes inhabiting a tract

of country nearly bordering on the Gulf of

Guinea, who, as he told my father, had been a

general in his own land,

before he was stolen from thence - (which was about the year 1780,)

and

brought over the vast Atlantic, with many others of his countrymen and

countrywomen,

and sold as a slave on a plantation in the valley above

mentioned. Reflecting often on the

high position he had occupied in his

native country, he bore the iron yoke of slavery with

much uneasiness;

and from the turbulent spirit he frequently exhibited, he was always

considered by his owner as a dangerous slave, he died at an advanced age

two years after the

Emancipation. My father's mother - from whom I

received some information respecting the

customs and manners of her

country Dahomey, lived much longer. Of my maternal

grandparents, as they had died before I was born, I know comparatively nothing.

During the period of my childhood there was no school in the country

districts, to which the

children of the people of my race could be sent

to receive the elements of useful learning; but

my father, having been

taught to read by a kind book-keeper on the plantation on which he

was

'headman', endeavoured to teach my brothers and myself to read. Books

were then

scarce: Fenning's and Dilworth's spelling-books were then, by

us, thought of the highest

excellence. After making some progress in

these, I was considered by my kind-hearted father

so good a scholar,

that he thought me fit to read the New Testament and an old edition of

Gurthrie's Geography. These were for long time my whole stock of school-books...

For four years, viz., from 1835 to l839, my teacher was my beloved

father, my school-books

those above mentioned, and my school, some shady

tree in my father's field, under which I

sat learning the lesson he

appointed me, to be repeated to him whenever he could

conveniently

attend to me. It will at once be seen that at such a school, and by such

a mode of

tuition, I could make but little progress in learning still I

must own that I derived much

benefit therefrom; for having been so

early thrown, as it were, on my own resources, I then

acquired that

taste for reading, and a habit of reflecting on whatever I read, which

have

always been of the greatest service to me in endeavouring always to improve my mind.

In the year 1839, the Church Missionary Society established a

mission and school at

Woodford, two miles distant from my native place.

That school I attended for about a year.

On my father leaving that part

of the parish to settle in another district, I was taken along

with him,

and as there was no school near our new home to which I could be sent,

he resorted

to his old plan of teaching me himself. Finding that by that

way I was making no progress, he

sent me to remain with a relative

residing near Woodford, by which means I was again

enabled to attend

that school, and where I received such little instructions as were then

given

in the country schools generally. As my attendance at school was

irregular - having been

absent therefrom at times for six months

together - although I had a thirst for learning, my

progress was not

satisfactory. In the year 1847 having, by some answers in geography,

attracted the attention of the Rev. (now the Ven.) W. Rowe, then Curate

of Woodford, he

promised my father to recommend the Board of Education,

to send me to the Government

Normal School, then recently established

near Spanish Town, to be trained as a teacher. On

14th February of the

following year I was admitted as a student into that institution, in

which I remained however, but eighteen months, having been sent for by

Mr. Rowe to take

charge of Woodford School, on the mastership of it becoming vacant in July, 1849.

A school in the country

The teacher.

After labouring at Woodford for seven years, in September, 1856, I

obtained the more

important situation of the mastership of the Church

School, Trinity Ville, Blue Mountain

Valley under the management of the

Rev. W. Stearn. It was while residing in this place,

where Nature is

seen in all her loveliness and sublimity, that I felt an ardent desire

to express

in verse the thoughts I had always, from my childhood, so

strongly entertained of Nature, of

Nature's God, and of the cruel wrongs

inflicted on my race. In 1862 I published 'The Slave',

and minor poems,

and two years after, 'Time and Eternity.' These little publications

having

met with much success, I have been induced and advised to collect

all my principal poetical

writings and publish them in a single volume.

Although conscious of many shortcomings, I may be pardoned in saying

that I look back with

some degree of satisfaction on the twenty- five

years I have spent in endeavouring to instruct,

in useful learning,

hundreds of the rising generation of my native land; and I have further

the

pleasing satisfaction in knowing that, by Divine aid, many of those,

who in years past were

under my tuition, have now become useful, intelligent, and respectable members of society.

Matthew Josephs and some of his opinions.

. . . And here I may observe in passing, that many have asserted that

the negroes have but

little desire for intellectual improvement. Had

those persons who hold this crude and

erroneous opinion known the many

strenuous efforts made by my father, labouring under

difficulties, to

instruct his children, although his own acquirements were extremely

limited,

they would have greatly qualified their assertion, so unjust

and so unfounded. The love of

knowledge is peculiar to no particular

race or nation. It is a principle implanted in every

human breast, for

the noblest purpose by the Allwise Creator. The presence or absence of

noble incentives are the chief causes why some nations are found in the

van of human

progress, and others, after reaching a certain height in

civilization, relapsed again to a state

of barbarism . . .

MATTHEW JOSEPHS.

December 1875.

(from the Autobiographical Preface to Wonders of Creation, the book of poems he published

in 1876.)

Poems by Matthew Josephs

1874

Again returns the happy morn

When here the Slave did cease to mourn;

When Peace and Freedom, hand in hand,

Came smiling o'er this happy land.

Oppression fled and sought the main,

Injustice followed in his train;

And as they left our lovely land,

Peace held on high her golden wand.

Now happy in his pleasant home,

Where wails of woe can never come;

The Freedman lifts his song on high,

To Him who reigns above the sky.

Around him press a youthful band,

To these he explains heaven's high command;

And kneeling lifts his voice in prayer,

Devotion melts his heart to tear.

Brightest of happy days, farewell!

No mortal tongue can fitly tell,

What happiness attends thy train;

Long may she here with peace remain.

And when again thou seek'st our isle,

And passing, sojourn here a while;

Oh! from that blessful [sic] home above,

Bring heavenly joy and heavenly love.

1874, of course, was the 40th anniversary of the legal ending of

slavery in 1834, so there was special cause for celebration, but Matthew

Josephs had already written

a longer poem for August 1 1872, one verse of which runs:

Here, though the days of wealth are past,

Though oft our sky with gloomy clouds o'ercast;

Freedom's bright happy era brought

Pure joy and peace to every heart.

The slave disdained

His cruel chain;

The man has claimed

His rights again.

. . . . . . . . . .

In Woodford's sweet, delightful vale again

The village school appears, where oft I joined

In songs of praise to Him who reigns on high.

The pleasant playground still is there, where oft

When from our tasks released, a joyous band

Of happy children met in innocent

And gladsome mirth, and made the vale

Resound afar with childish melodies;

While looking on, with countenance serene,

The loving Teacher, who the happiness

Of all his tender charge did ever share,

Matthew Josephs died in 1901.

AN APPRECIATION

MR. MATTHEW JOSEPHS

(By Young Liberal)

By the death of Matthew Josephs, there has

departed an honoured member of the Teaching profession, and a man who

was a credit to the Negro Race. I met him once in Kingston in the year

'93, and his form still lives in my memory. Matthew Josephs was born at

Rose Hill, October 1831, of slave parents, and was taught by his father

to read the New Testament (in spite of the many difficulties inseparable

from the system of slavery). Subsequently, he was sent to Woodford

School, and thence to the Government School at Spanish Town, in 1848. He

took charge of Woodford School in 1849, where he remained for seven

years, and then went to Trinity Ville in 1856. Here he wrote "The

Slave," published 1862, and "Time and Eternity," published 1864. He was

for some time master of the Chapelton School in Clarendon. Encouraged by

friends and well-wishers, he collected all his poetical writings into

book form, and visited England for the purpose of arranging business

with his publishers. The preface was written by the Rev. Robert Gordon,

for some time master of the Wolmer's Grammar School, then residing in

England.

His longest poem is "The Wonder of Creation."

Mr. Josephs took an interest in home

politics and was for some time member of the Parochial Board of St.

Andrew. It is to be hoped that at the conference of the J. U. T. for

1902, the Executive will pass a resolution in connection with his death.

Although he is only a Jamaican, he merits it; being one of those of

whom we may be justly [proud]. "Think nought a trifle, though [it sma]ll

appear; small sands make t [all] mountains, moments make the years, and

trifles, life."

The life of Josephs i[s to] a certain extent inspiring. True he was

no genius; yet still, if we look at the obstacles he had to overcome to

attain to the position he secured, he is nothing if not extraordinary.

And yet there are a few, a dwindling a few, thank heaven, who speak of

the "inherent inability of the Negro Race!" I am always quick to

recognize worth and worship the man, the hero; but if ever there can be a

brighter glow in my breast, it is when I contemplate the success,

however small, of one belonging to the African Race.

YOUNG LIBERAL

"Jamaica Times", 1901 Nov. 9, p. 2 col 1-2

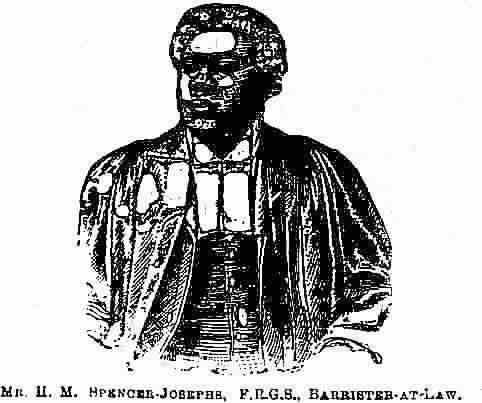

H M Spencer Josephs was the son of Matthew Josephs.

I have not found a photograph of H M Spencer Josephs, but I was very

pleased to find this line drawing. Spencer Josephs was a teacher for a

while, and also from 1890 to 1896 a land surveyor. In 1896 he went to

London and read for the bar; he returned to Jamaica in 1899 as a fully

qualified barrister. He was also a prominent Freemason. He died in 1903.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

'Oh, these God-sent teachers . . . . of rural Jamaica, in those opportunity-starved years

of the early nineteen hundreds.'

J. J. Mills - His own account of his life and times. (Kingston, 1969), page 41.